By Lora Chizmar

In today’s era of supplements and performance research, people are constantly looking for the next big discovery that will give them a greater edge in training. Money is spent on exotic protein powders, schedules are revised to allow for increased sleep, new workout regimes are adopted, and macros are calculated down to the gram. Yet, one of the most easily manipulated factors, hydration status, is often left disregarded and unconsidered.

Got water?

Despite the hardened appearance of a well-muscled body, the human body is approximately 60% water.[1] Among other functions, water helps us to get nutrients to our muscles, maintain our blood volume, and regulate body temperature through sweating. When exercising, dehydration can lead to less blood available for the heart to pump (decreased stroke volume). This condition leads to higher heart rates to compensate. In addition, the associated decrease in sweat rates lead to increased core temperatures and heat-related symptoms.[2] Mentally, dehydration can lead to increased perceptions of fatigue and effort, as well as decreased focus, coordination, and response time.[3] To put this in perspective, Judelson, et al. (2007) found that dehydration lead to a 2% decrease in strength, a 3% decrease in power, and a 10% decrease in high-intensity endurance![4] No thanks…Pass me the water jug.

Just tell me what to do.

Everyone dehydrates at a slightly different rate while exercising. These differences are primarily impacted by sweat rate. Haven’t you ever wondered why you are barely sweating, while the guy lifting next to you looks like he just got out of a pool? Sweat rate may vary based on body size, genetics, and fitness level, among other factors.[5]

So, how can you tell how hydrated you are? There are two simple tests to monitor your hydration state. The first is to weigh yourself immediately before and after a workout to see the exact quantity of fluid lost during the exercise bout. A more rudimentary option is to monitor urine color. A pale yellow color (good) indicates a more hydrated state, whereas a darker yellow color (not so good) is indicative of a greater state of dehydration.[6]

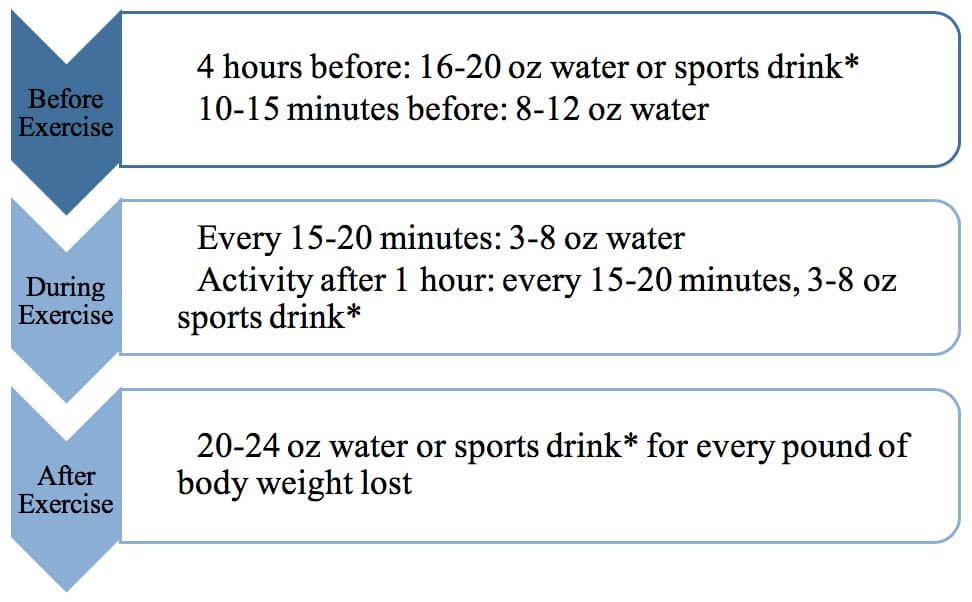

Interestingly, current research has shown that when drinking water is based on the sensation of thirst alone, the amount of water consumed is not adequate to maintain a hydrated state.[7] To aid us mere mortals in our muddled attempts to stay properly hydrated while training, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has published a set of general hydration guidelines for optimal exercise performance[8]:

*ACSM recommends a sports drink with electrolytes and 5-8% carbohydrates.

Keep in mind that some people may need more or less than the recommended amounts of fluids. Nonetheless, these guidelines are a basic tool to check your current hydration habits and make some adjustments where needed.

Plain old water, too boring?

Even if you are now convinced that you need to step up your hydration game, water’s neutral taste can be a turn- off. This is especially evident when competing against the lively flavors of juices, sodas, and iced coffees. If you are among those struggling to consume adequate amounts of water, try mixing it up with some natural flavor. Adding fruits like lemon, lime, or various berries to your water can brighten up the taste. If you are feeling fancy, try slices of cucumber. Herbs and spices are also options, with mint, lemongrass, and ginger being popular ways to change the flavor of water. You can make it more appealing to your palate without adding the extra calories and sugars of artificial flavorings.

(Lora Chizmar is receiving her degree in Sport & Exercise Science from the University of Central Florida. She is obtaining the ACSM Exercise Physiologist Certification upon graduation.)

[1] Penney, S. (2014, January 17). Hydration for Health and Performance. Retrieved from NASM Blog: https://blog.nasm.org/nutrition/hydration-health-performance/

[2] SDA Blog. (2016, September 14). Hydration: How much should you drink during exercise? Retrieved from Sports Dietitians Australia: https://www.sportsdietitians.com.au/sda-blog/hydration-during-exercise/

[3] Penny, Hydration for Health, NASM Blog.

[4] Judelson, D. A., Maresh, C. M., Anderson, J. M., Armstrong, L. E., Casa, D. J., Kraemer, W. J., & Volek, J. S. (2007, October). Hydration and Muscular Performance. Sports Medicine, 37(10), 907-921.

[5] SDA Blog, Hydration: How much, Sports Dietitians Australia.

[6] American College of Sports Medecine. (2011). Selecting and Effectively Using Hydration for Fitness. Retrieved from https://www.acsm.org/docs/brochures/selecting-and-effectively-using-hydration-for-fitness.pdf

[7] Armstrong, L. E., Johnson, E. C., & Bergeron, M. F. (2016, June). COUNTERVIEW: Is Drinking to Thirst Adequate to Appropriately Maintain Hydration Status During Prolonged Endurance Exercise? No. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 27(2), 195-198.

[8] American College of Sports Medecine, Selecting and Effecitively Using.